Shock and sadness

In Augusta, home to the Masters, residents talk about fright and damage of Hurricane Helene

Editor’s Note: In the aftermath of the damage left by Hurricane Helene, Augusta National Golf Club, the famed course that annually hosts the Masters, sustained significant damage and is working to repair the course while also committing $5 million to the recovery of the community. This story highlights the city of Augusta, Ga., and the destruction the hurricane wrought in the area, but the storm’s impact was widespread and severe throughout the southeast United States. Readers interested in helping can donate to trusted disaster relief funds in North Carolina and Georgia.

One of the two most frightening aspects of Hurricane Helene's impact on Augusta, Ga., in the early morning hours of Friday, Sept. 27, was that it came as a near-total surprise. As detailed in the Augusta Chronicle, the inland city of roughly 202,000 is "used to being a sanctuary city for disaster victims who more typically flee Georgia's coast," and not the site of the disaster itself. Warnings were issued both before and after Helene's landfall, but for areas of the country like Augusta and western North Carolina, which haven't experienced anything remotely like this level of devastation from a hurricane in a century or more, it was difficult to grasp the impending danger.

Dr. Bran Cromer is an associate professor of Biology at Augusta University and previously spoke with Golf Digest for a 2022 story about birds at Augusta National. Like many others, he was taken almost totally by surprise when the storm hit his home just over the South Carolina border in North Augusta that Friday morning.

"We're two, three hours from the coast," Cromer said. "Even if it's a pretty big hurricane, it'll be a weak tropical storm when we get it. But this thing came in so fast. We thought maybe we would miss Friday of school and be back on Monday."

A week later, Cromer's house still had no power. He counted himself lucky, though, because his university had power, and unlike 60 percent of the city, he had clean drinking water that he didn't have to boil.

Sarah Hall lives downtown, just off Augusta's historic district, and she also remembers wondering if school would be canceled for her two children.

"Everybody was saying it wasn't supposed to hit Augusta as bad, and that it was going to turn," Hall said. "People hadn't gone and got water and food beforehand. They hadn't got candles, weren't boarding up windows or anything. We weren't all prepared. We didn't know it was going to be that bad."

Being close to a hospital, Hall got power back quickly, but she still gets an advisory each day that she should boil her water and avoid eating ice. You wouldn't want to drink it anyway, she said, because it comes out brown.

The other most frightening part of the ordeal, and by far the most visceral, was the wind. Hall's house is a Queen Anne built in 1886, and when her 10-year-old son Nathan and 11-year-old daughter Anna woke her at 2:30 a.m. Friday morning because the noise of the wind wouldn't let them sleep, they could feel the house shaking, like it was shifting back and forth. They went downstairs to be away from the windows, and Hall wanted to see just how bad it was.

"I thought, like an idiot, 'I'm just going to look outside,'" she said. "So I opened the door, and the wind is like a wall of wind. It just blew the door open and blew me backwards."

Before they could close the door, they saw three light posts on the street fall over and noticed that the furniture on their neighbor's porch had flown off. Looking out a window, Nathan pointed to the sky and told his mom there was a spaceship in the sky.

"I was like, 'there isn't a spaceship up there.' It was just that the sky was blinking this neon green, blue color because of all the electricity and everything in the sky. It was just this really eerie color in the sky at that moment, and we were like, whoa, this is really bad."

At that point, her children asked her if the house was going to blow away, and if they were going to die.

Outside, the gusts they were hearing were later estimated to have risen as high as 100 mph.

Stacey Hayden is the vice president of Tournament House & Events LLC, which works with more than 2,000 Augusta residents to rent out their homes during Masters week. She lives in Augusta’s West Lake neighborhood and lost power for more than a week. She woke up around 2 a.m. on the 27th, got her teenage kids out of bed and moved downstairs, where they watched the storm through the window and prayed.

"It was very loud," she said. "It sounded like a train was coming down our street."

"The sound of the wind was like a train horn," Sarah Hall remembered.

"It was just a steady roar," said Bran Comer. "I don't know if I've ever experienced wind like that before, where it's so loud."

IT WAS THE TREES THAT did the damage. For Cromer, the wind was so loud that he didn't hear the massive trees falling. By 7 a.m., the worst of the destruction was over, and he was anxious to get out, especially to see about his mother, who lived in the city and was on oxygen (he was eventually able to reach her and ensure she was OK). When he looked outside his door, all he saw at first was his neighbor's basketball goal lying on the ground. Maybe, he thought, it wasn't so bad.

"Then I started scanning the street, and the neighbors' trees were down everywhere," he said. "And then we went to our backyard, and we have some pine trees about 70 years old or so, and four of them were uprooted."

Comer's theory is that the steady rain that Thursday—in all, around 8 to 10 inches fell on Augusta—softened the ground, and made easy work for the wind. From the destruction he saw, most of the trees that had fallen were fully uprooted rather than snapped.

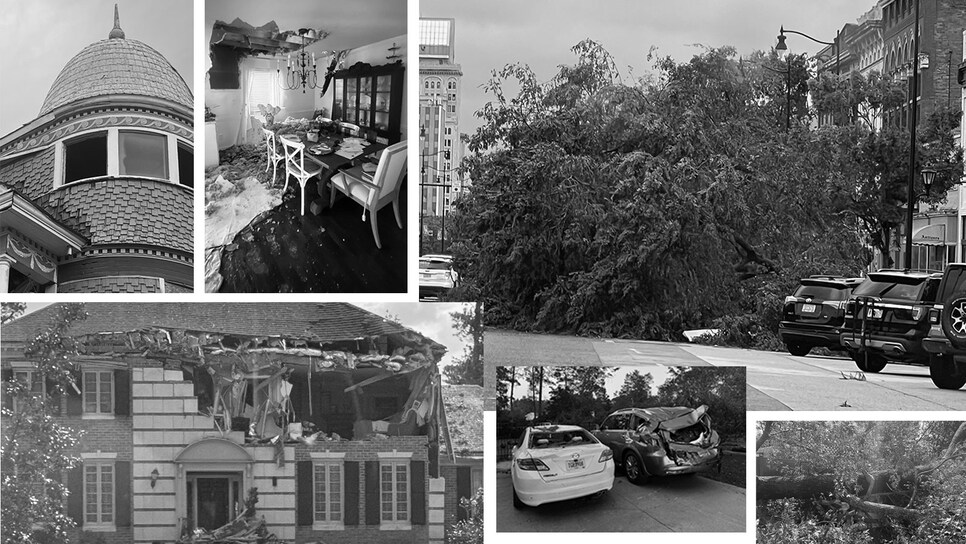

Sarah Hall's home suffered chimmy damage. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Hall)

Downed power lines can be found throughout the city of Augusta. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Hall)

No one escaped the issue of fallen trees. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Bran Cromer)

It's hard to see the car that's been almost completely covered by this fallen tree. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Bran Cromer)

It was the trees, too, that made life difficult for local golf courses. Chris Verdery is the director of golf at The River Golf Club in North Augusta, less than five miles as the crow flies from Augusta National. Like the others who spoke with Golf Digest, the sound of the wind woke him up on Friday morning, and there was never a thought that he could get back to sleep. By Friday afternoon, he was able to walk to his golf course, where he found more than 200 trees down on the property.

As it turned out, The River Golf Club was luckier than most. Once Verdery got everything approved with his insurance company, he hired a group of tree workers to take out the fallen trees (he has an open tab with them that is now into the hundreds of thousands of dollars). Though it took them a week, the course opened nine holes Oct. 4—even before power was restored. Power is back now, and the full 18 holes are open, though perhaps unsurprisingly the course hasn't been very busy yet. Verdery said he knows of other courses in the area with more than 1,000 fallen trees on the property and no power to speak of. They aren't open yet, and it will likely be a long time before they will be.

In other parts of Augusta, residents suspected that tornadoes had touched down. Hall was among those who felt what she thought were gusts that had to be tornadoes.

"It wasn't just that push of wind," she said. "It was all these other little tornadoes within it as it came through. And that was what was the most frightening, because the wind was changing directions. It wasn't just from one side to the other. We were getting hit from the back of the house just as bad as the front of the house."

Unlike Cromer, Hall heard the trees breaking during the peak hours of the storm. "It was like hearing bones crack," she said. "Our massive tree in our backyard cracked and fell over and it just went scraping down the side of the house."

"You could hear the pine trees snapping," Hayden said. "It was like PTSD from the ice storm a few years ago [in February 2014, when damage to Augusta National’s famed Eisenhower Tree forced the club to remove it]. You could just hear all the limbs snapping and breaking, and you could hear them crumbling through houses."

Hayden removed a trio of pine trees from her lawn a few months ago—she was tired of the pine needles—and is certain that if she hadn't, they would have crushed her house. Cromer had his old pine trees uprooted in his backyard, but he had two large pines in his front yard that never fell, including one just a few feet from his bedroom. Hall's tree scraped the side of her house, her attic windows blew out and shattered, her siding stripped, and one of her chimneys split in half.

'You could hear the pine trees snapping. You could just hear all the limbs snapping and breaking, and you could hear them crumbling through houses.'—Stacey Hayden

All of them know they were among the lucky ones. Exploring their neighborhoods, each told stories of pure devastation—trees that crashed through houses, stores, power lines and parked cars. Many traffic lights had come down, and as Hayden said, some were not just down, but completely missing, apparently blown so far away as to be unrecoverable. As the Augusta Chronicle reported, across Georgia more than 5,000 power poles and 500 transformers had to be replaced or repaired, and more than 1,500 trees had fallen directly on power lines. Along with power outages that affected (and in many cases continue to affect) tens of thousands of residents in Richmond, Columbia and Aiken Counties, damage to city water infrastructure has many residents still under an advisory to boil water. Needless to say, cell service has been spotty at best, and nonexistent at worst.

Stacey Hayden awoke the morning after Hurricane Helene to see this destruction near her neighborhood. (Photo courtest of Stacey Hayden)

Photo courtesy of Stacey Hayden

Anything uncovered in Hurricane Helene's path was vulnerable. (Photo courtesy of Stacey Hayden)

A curfew was enacted that first weekend, in part to stop looting across the state, and in some cases law enforcement had to be called in to maintain order at the few gas stations open to the public. There have been cases of the ugly profiteering side of human nature rearing its head—goods like fuel offered at high prices by unlicensed vendors, out-of-town companies coming in to remove fallen trees at exorbitant prices. Yet all three residents Golf Digest spoke to pointed to the heartening way the community had come together in the aftermath. Thousands of linemen came in and are working 15-hour days to restore power. Churches are distributing food, water and other supplies. Government aid on both the national and local level is rolling in, restaurants are feeding residents, and neighbors are helping each other whenever they can.

Hall's parents, who now live in California but have a rental property in Augusta, have opened up their home to families who lost their own houses to the storm. Hayden's son, who has a forklift license, has been out helping the tree crews. ("All you can hear right now are chainsaws, everywhere," she said.) Cromer was helping a neighbor across the street clear debris when a few people from a local church stopped and asked if they needed help; soon, they called others, and 10 people showed up to help haul off logs and brush. The Ironman competition was supposed to be held, and when it was canceled, organizers drove around giving out their significant supply of water.

Even with this infusion of community spirit, and acknowledging that the devastation has been worse elsewhere, the effects on Augusta and Georgia generally have been shocking. Statewide, there have been at least 33 deaths. In Augusta, where the poverty rate is higher than the national average, the personal and economic damage can't truly be calculated yet.

Hayden has a unique perspective on this through operating her rental business, with her clients often fetching five- or six-figures for renting out their homes for Masters week. When COVID hit in 2020 and caused the Masters to be delayed by six months, and then held without fans, she saw several homes being sold when the money the families counted on failed to come through. Already, she's heard from homeowners whose houses have been destroyed and will lose that income for 2025. The best they can hope for is to fight a dubious battle with insurance companies to be reimbursed for lost income.

Which, compared to some of their neighbors, will seem like a trifling problem. Schools are supposed to reopen this week and power is being restored. By next April, when the Masters is held, there will undoubtedly be uplifting stories galore. But it will exist in the shadow of everything that's been lost, in Augusta and across the southeast, from a few hours of devastation that took almost everyone by surprise.